How can organisations proactively look forward to identify future opportunities and threats? This series of five short think pieces examines some of the key ways that organisations can reduce the level of uncertainty surrounding what’s next.

#4: Find out what you don’t know

Author: Richard Watson

Beyond thinking about your own thinking and thinking through whom you speak to and how you illustrate your argument or ideas, what else can you do to avoid being caught on the wrong side of future history? According to Michael Laynor at Deloitte Research, strategy should begin with an assessment of what you don’t know, not with what you do. This is reminiscent of Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous ‘unknown unknowns’ speech.

“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know….”

The language that’s used here is tortured, but it does fit with the viewpoint of several leading futurists including Paul Saffo at the Institute for the Future. Saffo has argued that one of the key goals of forecasting is to map uncertainties.

What forecasting is about is uncovering hidden patterns and unexamined assumptions, which may signal significant revenue opportunities or threats in the future.

Hence the primary aim of forecasting is not to precisely predict, but to fully identify a range of possible outcomes, which includes elements and ideas that people haven’t previously known about, taken seriously or fully considered.

The most useful starter question in this context is: ‘What’s next?’ but forecasters must not stop there. They must also ask: ‘So what?’ and consider the full range of ‘What if?’

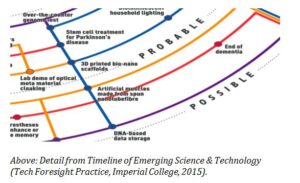

A key point here is to distinguish between what’s probable, and what’s possible. Sherlock Holmes said that: “Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.” This statement is applicable to forecasting because it is important to understand that improbability does not imply impossibility. Most scenarios about the future consider an expected or probable future and then move on to include other possible futures. But unless improbable futures are also considered significant opportunities or vulnerabilities will remain unseen.

This is potentially moving us into the territory of risks rather than foresight, but both are connected. Foresight can be used to identify commercial opportunities, but is equally applicable to due diligence or the hedging of risk. Unfortunately this thought is lost on many corporations and governments who shy away from such thinking or assume that new developments will follow a simple straight line.

What invariably happens though is that change tends to follow an S Curve and developments have a tendency to change direction when counter-forces inevitably emerge.

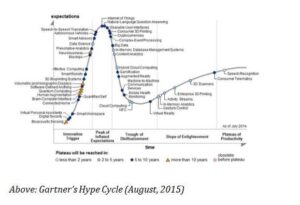

Knowing precisely when a trend will bend is almost impossible, but keeping in mind that many will is itself useful knowledge. The Hype Cycle developed by Gartner Research (below) is also helpful in this respect because it helps us to separate recent developments or fads (the noise) from deeper or longer-term forces (the signal). The Gartner diagram links to another important point too, which is that because we often fail to see broad context we have a tendency to simplify.

This means that we ignore market inertia and consequently overestimate the importance of events in the shorter term, whilst simultaneously underestimating their importance over much longer timespans.

An example of this tendency is the home computer. In the 1980s, most industry observers were forecasting a Personal Computer in every home. They were right, but this took much longer than expected and, more importantly, we are not using our home computers for word processing or to view CDs as predicted. Instead we are carrying mobile computers (phones) everywhere, which is driving universal connectivity, the Internet of Things, smart sensors, big data, predictive analytics, which are in turn changing our homes, our cities, our minds and much else besides.

Next post: Drilling down to reveal the real why

This post was written by Richard Watson, who works with the Technology Foresight Practice at Imperial College