Including Privacy in Human Interaction by Design

Author: Germán León

The amount of time we interact with screens in our daily life is at an all time high. Already the gross of our on-screen time is spent on mobile devices instead of desktop computers. We expect near-seamless transitions between modes, that an experience we started on a mobile device (booking a flight, shopping for an item, researching work) can be continued and completed on a desktop computer or smart TV and vice versa.

Smartphones are ubiquitous, yet our interaction with devices is still largely separated from social and human interaction. Just think of a dinner with friends: you can either have a conversation, or you can have your device in hand.

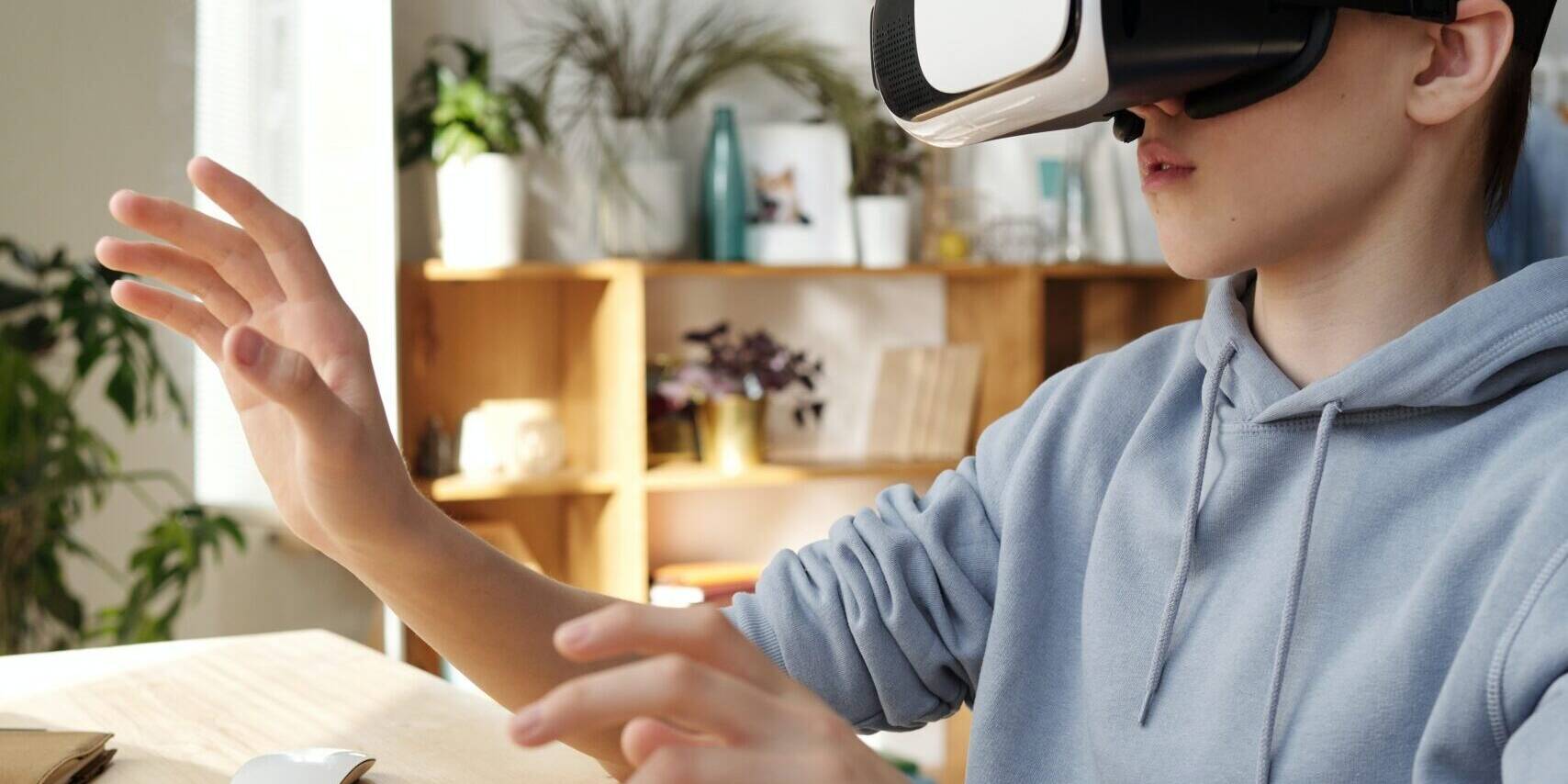

But now we are facing a paradigm shift. Through smart devices and wearables we are already getting used to technology with no graphical user interface which integrates into our lives without on-screen interaction. This is complimented by devices and no longer centered on one particular user or owner, such as smart technology in and around our homes in the form of thermostats, TVs, vehicles, Amazon Echo ? even in public spaces in the form of embedded systems, sensors, and cameras.

Our way of interacting with this technology, the so-called Internet of Things, will be fundamentally different. Just like the sit-down experience of mouse and keyboard has become the more mobile touchpad and gesture interaction, we will interact with surrounding technology in full 360 degrees, both consciously and unconsciously.

The collective services of the Internet of Things are engineered with just-in-time delivery of what we need, predicting and anticipating our needs ahead of our own awareness of them. For this, they rely heavily on the gathering, collating, correlating and analyzing of user data on a large scale, otherwise known as Big Data.

In a world where we can no longer make any conscious choices in the way technology processes and interpretates the data of collective individual interactions to form an understanding of human behavior, we have to raise the question of privacy of human interaction.

The Privacy Controversy

As users, we value a personalised experience where we are presented with offers and results relevant to us, ideally at just the right time, exactly when we need them. At the moment, we know and use these as personal assistants in the form of Google Now, Siri and Cortana to provide us with electronic tickets, traffic updates and travel predictions.

When it comes to privacy, our behavior is controversial. We are willing to give away some private data in exchange for these services for free, yet many of us admit they are weary when it comes to sharing private data, the very building block that enables personalized services. Then again, services with privacy features at their core seem to suffer a niche existence at best, far from mass adoption. Examples here include the social network Ello, messenger services like Cryptocat and Zendo, or the Blackphone, a pro privacy smartphone. Everyday users prefer the ease of Facebook Login to more anonymous alternatives and favor WhatsApp over competing messenger apps with better encryption and privacy features.

As Big Data is moving forward to include information fed from an abundance of nearly omnipresent sensors, cameras, and microphones, a vast amount of human interactions can be captured. From their analysis, patterns of human behavior emerge. As users, we have an understanding that the accuracy of these patterns determines just how useful Big Data reliant services are. We are not averse to this reciprocity: to get something personal, we have to share something personal.

But when data collection goes beyond that, users feel their privacy ? and their right to privacy ? are being infringed on. Services collect more information than they need to fulfill their purpose; data correlation can single out individuals despite anonymous collection; companies snoop on the data, messages or images they transmit, and pass collected data on to third parties, be it advertisers, other corporations, or even governments. All of these raise privacy concerns.

From a user perspective, two things seem certain:

we cannot expect corporations to uphold our privacy demands. Big Data allows for a wealth of innovation and improvement of user experience on the one side, but comes with great possibilities for monetization tied to privacy infringement on the flip-side;

we cannot expect governments, law- and policymakers to keep up with the pace of invention and innovation. Technology companies move with a can-do attitude, implementing what is possible.

The duality of users being served and used at the same time will continue to be in the interest of technology companies. Faced with data collection on the large scale of the Internet of Things, how can users regain control of their privacy?

The Death of GUI and Putting YOU in UI

The paradigm shift which begun with the Internet of Things with its surrounding technology and constant interaction in 360 degrees, has moved beyond the traditional graphical user interface, culminating in the disappearance of the GUIas we know it today.

At the moment, we still rely on opt-out possibilities to protect our privacy and tailor the user experience to our liking. We can still choose the degree of tracking through location services, cookies and smart gadgets. We can still choose not to use predictive services or opt out of sharing our fitness data, shopping history and other gathered information. At the most drastic, we can stop wearing devices and forego our smartphones. But that implies ownership or at least access to the technology.

In a world saturated with sensor technology, exposure to it is beyond our control. Our human interaction with technology is no longer a dedicated session initiated by us, it is constant and multi-modal and often not apparent to us. We are interfacing with technology with our very being, we are part of the UI. Will our possibilities to opt out be reduced to razzle dazzle camouflage to avoid camera detection and total abstinence?

Designing for Privacy

We believe there is another way forward. We call it the principle of Privacy by Design. We believe that privacy concerns and therefore privacy experts need to be included in the development cycle of every product or service from the very beginning. Privacy can no longer be an afterthought that is being added to a minimum viable product after it has been launched.

On one hand, being surrounded by smart devices, sensing technology and theInternet of Things is intrusive by nature as technology needs to be deeply integrated into our lives to deliver meaningful data on human interaction and behavior. On the other hand, the vast amount of data detected, collected, stored and analyzed is not inherently evil in itself. On the contrary, it is a building block of future innovation, allowing for insights into existing behavior and ultimately for life improvements through assistive and predictive technology.

As we move towards immersive technology with users themselves as the user interface, we need not question inevitable data collection, but ownership and access to what is being gathered. We believe that when you are part of the UI, your interactions and the resulting data are yours and yours alone. Sharing your data should be opt-in-based, with you giving authorization to institutions and companies for selective and clearly restricted access.

We are working on the first anonymized data platform that will sense, detect and respect the privacy of its users. Because we want technology to follow your definition of privacy instead of the other way round.